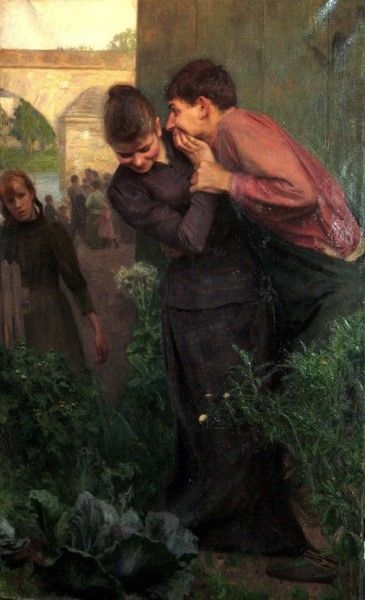

Premier Assaut, 1893

Premier Assaut

Oil on canvas

Signed and dated lower right E. Friant 1893

190 x 120 cm

Caught on the spot

We are very close to the Malzéville bridge, in a secluded garden, separated from the banks of the Meurthe by a high wooden palisade and a small removable fence on the left. A young man, eager and hasty to say the least (he hasn’t taken the time to put his shoes on, he’s wearing his slippers, his shirt has come off his overalls showing a little skin from his back), bursts into the painting and rushes to a young girl he probably knew he could find there, unless the two had arranged this meeting. He thinks he’s out of sight and tries to steal a kiss from her. The half-consenting, half-frightened young girl pushes him away while chastely turning her face away. She smiles as she is blushing. Neither sees the young teenage girl standing behind the small fence watching them with concern and curiosity. At the bottom left, in the very foreground, sits a magnificent cabbage surrounded by beds of chrysanthemums. It is the end of summer.

Let’s dwell on how Friant captures this scene. He chooses the vertical format, “à la française,” normally used for portraits and architectural elements. The size of the canvas is spectacular : almost 2 meters high by 1.20 meters wide. In fact, the critic Arsène Alexandre did not understand why the painter chose such a large format to paint “a vulgar rut scene at the corner of a wall”. Friant deliberately chose this very tight vertical composition, which, by cropping out the surroundings, allows the eye to focus on the strong points. By forcing the gaze upwards, Friant gives even more movement and strength to the embracing young couple, who seem to lose balance in a bold oblique. In addition, it helps the viewer to make the connection between the strong points and capture the entire symbolic of the work.

Two years earlier, Friant had already used this same vertical composition for another highly symbolic work, Ombres Portées, in a large but smaller format (musée d’Orsay, Paris)

Premier assaut shows Friant’s mastery of photography and ability to use it to his advantage. Far from getting blinded by the possibilities of this new technique, as it is still too often claimed, he skillfully uses it to break with conventions and bring twists and original points of view to his somewhat classical compositions.

Premier assaut does work as a snapshot of a scene caught on the spot. Through his composition, Friant gives the illusion of having captured this stolen kiss in the moment, like a paparazzo on the lookout for front-page scoops.

Now let’s see how Friant chose to place his characters : the couple occupies the right two-thirds of the canvas and the young adolescent the other third on the left. A vertical line, materialized by the edge of the wooden palisade separates two spaces : the first, where the couple believes to be sheltered, protected from the gaze of others, and the second where they fall victim, caught in the act by the young teenager. This second space is also split in two : it is the adolescent’s lookout position, while at the same time a place where she is herself observed, although she is not aware of it.

Tracing two diagonals across the composition sheds light on two triangular spaces. It is through the very elaborate interplay of lines of force and gazes that Friant insufflates life and naturalism to his characters. He gradually leads our eyes towards the attempt.

In the triangle on the left a little in the background, from the shadows, emerges the gaze of the intruder, the voyeur, the spy. The adolescent girl in the extreme left edge of the canvas suggests an off-camera, echoing in symmetry and simultaneity the loud irruption of the young man from the right of the painting.

In the foreground on the right, the couple forms a large triangle. In a very tight hand-in hand combat, their bodies seem welded, the young man’s right hand grips on the waist of the young girl, while his hand pushes the girl’s right hand away, as she attempts to move away from the lips of her assailant. All the forces and counter-forces from this part of the canvas create an effect of violence that was deplored by the critics at the time. The tilted upper bodies of the figures embody the brutal assault of the young man: the couple leans to the left, dragging in its movement the young teenager, also leaning as if realizing by ricochet the violence and epiphany of this attack. To reinforce the snap-shot effect, all the vanishing points meet beyond the canvas in the upper left corner.

Let’s not forget the magnificent cabbage surrounded by beds of chrysanthemums that sits in the foreground. It is connected to the couple through the plunging gaze of the girl who seems about to fall on him. Alluding the intrusive gaze of the man, she is watching the cabbage, itself an extension of the young adolescent’s body, thus creating another triangle, pointing downwards this time.

Symbolically and in popular folklore, the cabbage represents fertility, birth and death. The allusion to sexuality is therefore obvious and the presence of the cabbage functions both as a warning for the girl reminding her of what could happen if she gave in to her desires and as a riddle for the young teenager who of course knows the song, “Do you know how to plant cabbage in fashion, in fashion…. ?” and begins to question the relevance of the explanations given to children about the birth of babies who are said, for boys at least, to be born in cabbages.

Just take a look at the color palette. It too helps to create tension: it changes from the bronze green of the overalls to the yellow rose of the shirt and the purple of the dress and the cabbage, all surrounded by the lush green of the vegetation. Note that the color green, long before what we know today as the symbol hope and freedom, meant at the time instability, infidelity, as well as ephemerality of things like youth, vigor and love. Note the pretty bright yellow tips of the nascent flowers. Not only does the color yellow as seen in the pink of the shirt represent autumn, but it also symbolizes betrayal, infidelity, lies (in the 19th century, cuckholds were caricatured in yellow suits) and exclusion (the yellow star). As for the color purple that Friant commonly uses for his female characters, it symbolizes knowledge (in the biblical sense ?), as well as mourning or melancholy, hence its presence on the cabbage.

The play between the various lines of force and symbolic elements creates such a powerful effect of tension and instability imbued with truth and modernism, that the public and the critics were shocked at the time. Even the Parisian critics, “usually not very prudish, could not bear this spectacle and judged the subject vulgar, the interpretation brutal, indecent. […],” as read in L’Est Républicain, 26 May 1894. The presence of the cabbage as a reminder of the ephemeral nature of things, the colors’ symbolism, and the very striking realism of the subject certainly contributed to the public outcry, despite its great power and disturbing psychological accuracy.

Mô FRUMHOLZ-BURTIN

Translated from French to English by Agnès Penot